Selected excerpts from

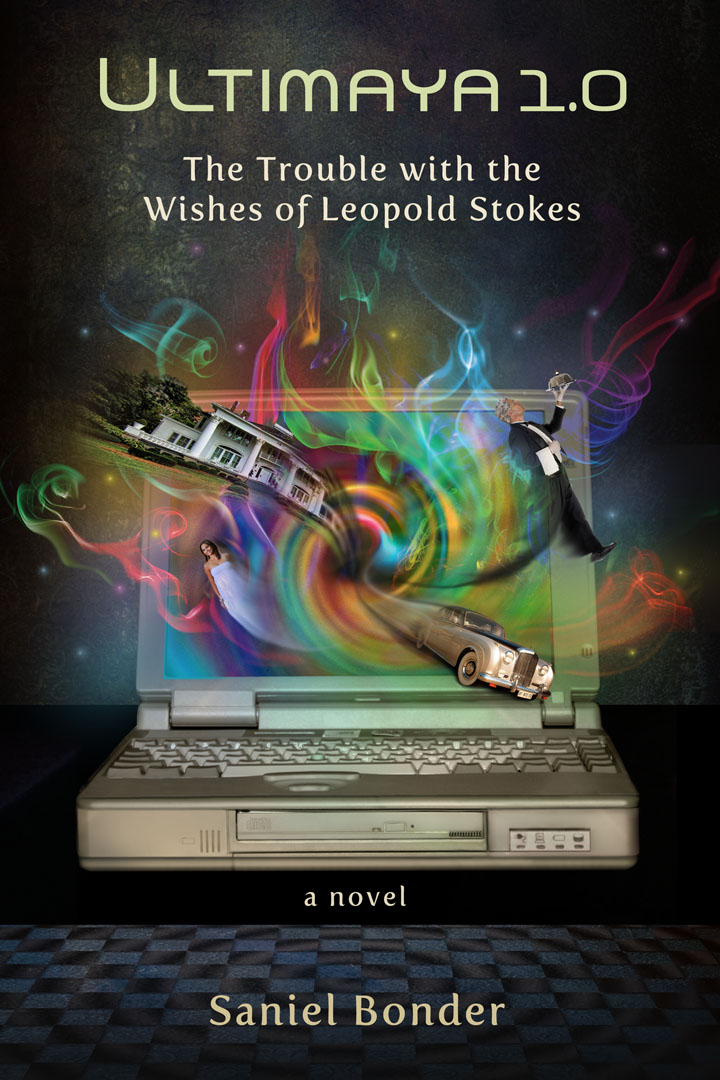

ULTIMAYA 1.0

The Trouble with the Wishes of Leopold Stokes

a novel by Saniel Bonder

Copyright © Saniel Bonder 2011. All rights reserved.

Dedicated to the memory and living spirit of my late father, Murray Bonder

And for everyone who’s trying to become happy by fulfilling wishes and making dreams come true

Dedicated to the memory and living spirit of my late father, Murray Bonder

And for everyone who’s trying to become happy by fulfilling wishes and making dreams come true

Note to the Reader: The following text includes all of Chapter 1 of Ultimaya 1.0, and portions of Chapter 12.

I’ve adapted and modified some of that chapter for these excerpts, mainly to make sure not to give away what happens in Chapters 2 through 11. Enjoy! ~ SB

1. Trouble

Leopold Stokes knew he was in trouble. Trouble was, he didn’t know what kind of trouble he was really in. He thought he knew. But he didn’t really know.

It had all begun the night before. It was a cold evening in December 1992, long enough before Christmas that Leo still couldn’t be bothered to think about it. He was at the table and Nan, as usual, was ragging him mercilessly with her pet naggation about his persisting singleness and obvious need for female companionship of his own age. She, of course, was only speaking to him because of her loyalty to his parents and their dear solemn memory. It had nothing to do with her own concerns. For all she cared, he could go solitarily to his grave–that was his business. But his momma had always been aggrieved over his failure to marry and have a family. Now that she was gone, well, she, Nan, felt she really had no choice but to continue to press the issue, even though she was not even family, she was really only a friend of the family. As Leo well knew–and Nan never failed to acknowledge at this point in her speech–she had only come to live with them lo these many years ago due to his momma and daddy’s kindness at a time of severe trials in Nan’s own life.

But Nan had been there at his momma’s passing. And his momma’s virtually last words, according to Nan, had been her plea to Nan to continue to remind, that was the exact term, remind her dear Leo to please find a wife and have some children. How else, his momma had worried, could Leo carry on the fine Stokes name that his poor daddy–and his granddaddy too–had labored so long and hard to bring to distinction there in Cotton County? (Leo always wondered about that phrase of Nan’s, “vur-choo-ul-lay last words”; if those weren’t his mother’s actual last words, then what exactly were?)

Well, right in the midst of Nan’s diatribe, Leo surprised even himself. He had by now virtually memorized her speech (there it was again, “vur-choo-ul-lay;” she said it so often and with such emphasis that he now, to his annoyance, found himself using it even in silent ruminations). He could recite her rant more or less verbatim, could interrupt her at any point and carry on without a hitch, and in fact often did so, rather politely of course, with downcast eyes–not wanting to mock her too much because that would really wind her up. And Nan would listen to every word, nod emphatically, and then, as if she had not given him the same shrill speech two thousand times, crow in response, “That is precisely what I was about to declare!”

But this time, instead of mimicking her, with both hands Leo yanked up the large, nearly empty casserole dish, lifted it two full feet into the air, and then let it drop, so that it smacked onto the solid mahogany dinner table with a tremendous whack. The whole table shook so hard that the slightly melted Jell-O sloshed over the edges of its bowl, and the remains then came to a tremulous rest in the bowl’s innards, as if still quaking in fear of Leo’s next potentially violent act.

Leo resisted the urge to grin and looked from the jiggling Jell-O to Nan. She too was tremulous–thin little mouth agape, narrow-set blue eyes stunned wide open, one pallid and blue-veined little hand frozen motionless on her gray bun, where it had been tucking in stray wisps when the crockery crashed to the table. This was a new and totally unforeseen event in Nan’s universe, and she was duly astonished. Knowing her resiliency in the–what did she call it–“give and take of life’s hick’ry switches,” Leo leaped into speech before she could gather her wits and start talking again. He looked her square in the eye and–pausing for just an instant to register her obvious discomfort under his glare, for she’d never anticipated he might silence her with such a look–he delivered his admonition with a deep metallic grind of threatening authority, so that each syllable was like a tank rumbling up to the border of the shrill little solitary spinster’s nation of Nan and taking dead aim right between her beady blue eyes.

“Nan…shut…your…gol-…dang…mouth!”

The “goldang,” which he’d added only to strengthen his point, sped right past her. Leo had the strange sense of the word missing its target and landing, mute and harmless, on the kitchen floor beyond her right shoulder, like a dud Iraqi Scud missile in the recent Gulf War. The thought made him want to laugh, but he suppressed it, didn’t even let his lips twitch into a grin. He did make a mental note to reserve what she called “shocking sinful speech of the Devil” for her less mind-shattered moments. Then he waited.

After a time, Nan closed her mouth and rather modestly–he even suspected submissively–turned her eyes away and down from his implacable gaze.

And after a few more crucial moments, for she could have gone either way, it was his turn to begin to feel a sense of astonishment, accompanied by elation.

It had worked. Nan wasn’t saying so much as a single word.

They both returned to their meals. Leo forced himself to breathe calmly, like nothing had happened. Nan didn’t look up. She didn’t even ask him to pass anything from his side of the table. Leo knew very well that on an ordinary night she would have gobbled down the entire bowl of black-eyed peas, and part of the standard evening lecture would have been a stern disquisition on the necessity of his eating his collard greens–“if you want to protect a body against heart disease in old age, a necessity you have never faced up to, not since I was young and purty and you were dressed in short pants, little man.” Tonight, mercifully, the lecture was cancelled, and Leo enjoyed the leisure of wondering for a few moments how she ever pieced together a connection between collards and cholesterol.

He glanced around the room a bit, seeing that some of the pine paneling was just slightly warping off the wallboard, and that the old red and blue Oriental rug that covered most of the oak floor was going threadbare in places. No surprise, he thought, remembering that his mother had had that rug in this dining room since his boyhood. Simultaneously he realized that during most of his meals with Nan these days he felt so set upon that he barely looked up from his plate to register anything around them. It occurred to him that he should replace the plain white ceiling fixture with something, well, something a little more modern, and that he should ask Nan to get some flowers for the center of the table (plastic ones would be okay, as long as they looked real). It would be good to have a new houseplant or two for the white-painted brick flooring in front of the unused fireplace and chimney, which were likewise of white brick. And maybe he ought to find a new painting for the mantelpiece, a colorful Matisse print perhaps; the stern photo of Abner Stokes Sr., his grandfather, might well deserve retirement, at least from such prominent display. Leo felt a pleasant surge of energy to change things. Indeed, he felt like it had been ten years since he had last even looked at the room.

Nan, meanwhile, averted her eyes for the rest of their dinner together. She ate in uncharacteristic birdlike nibbles, and soon retreated in silence to the kitchen and the dishes. She seemed so cowed that Leo almost began to feel sorry for her.

But then she began talking to him again, not with words, but nonetheless out loud. As Leo sat savoring his Maxwell House, he heard her begin to clang each finished plate and utensil into the dish drainer. With every one, it seemed, Nan put more force into her protest, so that he began to fear the dishes would break, or that she would hurt herself on a knife. He sighed, removed his orange paper napkin from his lap, and strode to the open kitchen door.

“All right, Nan…I’m sorry I yelled at you and used foul language.”

She did not look up. She was just then rinsing a large porcelain serving tray, and she held it up with both hands while looking for an open slot in the drainer. Then she smashed the tray into its slot so hard that several forks and knives bounced out of the silverware container and clattered onto the floor. Nan didn’t even look at them but only turned to clean her next victim, the big casserole dish.

Leo sighed again, this time aloud. “Come on, Nan, no hard feelings. Stop smashing that poor dinnerware around and talk to me again.”

No response. Nan continued to bend into the casserole dish, scrubbing it with the piece of steel wool as if to scrape the enamel right off. Leo knew what was coming next; it too would be crashed into the dish drainer, as would everything else left in the sink. Nan had been grievously wronged and he would be paying for it as long as she could find dishes to scrub that evening. Given her resourcefulness in such affairs, she’d likely find ways to keep him paying dearly a good deal on into the night. There was no room in the little two-bedroom brick house for him to get far enough away from the noise to be able to ignore her. And Leo knew very well that Nan knew very well that he decidedly did not like going out at night. He had no nighttime socializing friends to speak of. Ashlin had no bars, no nightspots, at least not with sufficient class for him to frequent–though he would never have dreamed of going to such a place anyway, at least not there in town. The library closed each evening promptly at six. And there was no way he was going to give in and call Constance, who was probably on duty at the hospital anyway.

Nan had him.

For an instant Leo wondered why his second command had not worked. He had told her to stop smacking the plates around, he had even told her to talk to him again. What about the program? What about Ultimaya 1.0? But in that instant the casserole dish came down onto the counter with a shocking crash, and Leo entirely forgot his grumbling wonderings.

In a flash he felt himself being overwhelmed by the kind of rage that his old friend since high school, Charley Bass, used to call “the Leo-nuclear weapon” or, for short, “the L-bomb.” He could feel the blood rushing to and reddening his already red neck and face, and the act of compressing his lips to keep from shouting somehow seemed to make his eyes bulge out–Charley had teased him about how his face and eyes got as red as his hair–and he knew he wouldn’t be able to hold it in. Even under ordinary circumstances he sometimes felt his thickset, strong body was as rigid as a brick chimney. And though he was incapable of radiating emotional warmth of a tender kind, when an explosion of anger started churning in his guts, Leopold Stokes could neither control nor contain the internal fires. Raging words and acts would burst out of him like smoke spewing into a room through faulty flues and cracked mortar. No matter how hard he tried to restrain himself, it never did any good.

Like right now.

Without a word, Leo smashed his fist into the kitchen door so hard that the door cracked back against the wall and then stood shaking on its hinges, reverberating. Leo looked in fury at Nan.

She had already picked up the frying pan and was scrubbing away, her back toward him and her head bent over the sink.

Leo glanced down at his bloody and bruised knuckles, which hurt so bad he had to fight back tears. He had a sudden sense of himself as a stick of dynamite with a half-inch fuse. His ears felt hot enough to blister; he knew he’d better get out of that room fast. But as he turned to go, he could not resist shrieking: “Nan, goldang it–if you don’t want to talk to me, then WHY DON’T YOU JUST SPONTANEOUSLY COMBUST!”

What happened next was something Leopold Stokes would not likely forget for the rest of his life. Just as he was about to stomp off, he noticed that Nan had stopped moving. She stood stock still in front of the sink. Then, with a clatter, the frying pan slid out of her left hand onto the dishes stacked underneath it. Her right hand still clutched the steel wool as she turned toward him, nothing moving except her feet and legs, the rest of her body frozen like a statue.

Leo felt the blood drain out of his face and neck. “Nan?”

She seemed not to hear him. In fact, she seemed oblivious to everything, even though her eyes were wide open and staring straight through Leo’s. Her gaze was so bizarre that he felt like a cornered creature. Despite his discomfort, he could not avert his eyes until something began to happen in her clenched right hand that distracted him.

The ball of steel wool in her hand appeared to be enveloped by a strange, bluish green light. As Leo looked on dumbfounded, strands of it began glowing orange and dissolving, until–with an almost silent poof!–the whole ball of steel wool burst into incandescent flame and then floated away in shreds of ash.

Leo hardly had time to register all that before he noticed that now the same bluish green light had extended up Nan’s arm and was enveloping her whole body. His mouth dropped open and he let out a gargled croak as it hit him what was about to happen. He reached for her with his undamaged hand in a desperate effort to somehow prevent what was coming, but then there was another, almost entirely silent–but this time monstrous–flash of light and heat that knocked him back through the dining room doorway and threw him flat on his back.

For a moment, Leo lay there disoriented. Then he remembered what was happening and sprang to his feet. The entire front of his body felt hot and singed, as if he’d been in front of a blast furnace. Trembling, he groped his way to the doorway again. It dawned on him that the room was so full of–what? Smoke? Soot? Ash? Whatever it might be, there was so much of it flying around, he could not see.

“Nan?”

The particles of ash were settling to the floor. Dark gray soot coated the walls all around the kitchen, including the dining room door and the refrigerator door, even obscuring all of Nan’s little scribbled yellow post-it warnings to him not to eat her private foods in the fridge.

“Jesus…what? What’s–Nan! Where are you?”

There was no answer. Leo struggled to make himself look at the floor where she’d been standing.

There was nothing there–except one little black old-lady’s shoe, kind of shapely and not too stodgy looking now that Nan wasn’t standing in it, with the brand name “P. W. Minor & Son” ash-dusted but still visible on the insole. The shoe was standing upright exactly where her right foot had been planted the moment before the explosion.

Leo gulped, croaked aloud, and began to shout. He threw himself to the floor, his hands outstretched so that both of them grasped the shoe without moving it, his face and whole body flat on the linoleum. Tears began streaming from his eyes, and he began to moan aloud.

“Aagh! AAAAAAGGGGGHHHHH!!!...Oh God, I’m sorry. I’m sorry. I’m sorry, God! NAAAAANNNN!! I didn’t mean it, Nan! I didn’t want to hurt you! You get on my nerves, but I didn’t mean for you to die! Nan! Where are you? God A’mighty, this can’t be true! Aagh! AAAAAGGGGHHHH!”

Suddenly, a thought struck Leo like a laser beam in his brain. He was quiet for a moment, the stillness broken only by his sobs and the snufflings of his nose. Then, still without moving, he said out loud, real loud, with all the ardent hope and need of his being:

“Oh God, if you exist–I know you exist–dear God, Lord of my soul, have mercy on me. Have mercy on me, Lord. I did not really mean for Nan to die. I did not mean to set her on fire. That was horrible, Lord. I mean, it was horrible! I would not wish that on anyone. I will not wish that on anyone. Never again. NEVER!!”

Leo paused. With a weird, oily sensation of being caught in the act, he felt he must have sounded like Burt Reynolds in the movie The End, bargaining with God when he thought he was drowning. Leo redoubled his efforts to be sincere, so that he was practically shouting:

“So please don’t let Nan die. If there is any way under the sun–under the moon and the stars–that You can bring Nan back to life, I swear Lord, I swear it on my mother’s grave, on the Bible, on everything I hold true and sacred, I swear it on the foreclosure notice I’m holding on that little country Baptist church–Lord, I will rip that notice up tomorrow morning, I’ll go down to the office and do it tonight! I’ll pay their rent myself for three months–but dear God, Lord of Hosts, Father of our blessed Savior, Jesus, yes, holy Jesus, You too, I beg You: Please, please, PLEEEAASE bring old Nan back to life. Don’t leave her dead, and me here to try to live my life now that I have made this terrible thing come to pass. I beg You, Father. I beg You, Jesus. I beg You. I beg You. I beg You!”

Leo could think of nothing else to add to his prayer. Despite his desperation, it still left him cool and a little queasy. And, as he lay there, his nose and face flattened on the linoleum, his outstretched hands cradling Nan’s one remaining shoe, he couldn’t help wondering: horrific as this moment was, what was the point of making such supplications at all?

After all, Leopold Stokes never had been more than a Sunday, preen-and-pray Christian. He’d been baptized, but it meant little to him. He just never could detect any “hand of God in human events,” no matter how hard he looked. So his point of view was, why bother with something that’s inconsequential–whether it exists or not?

In their teens, he and Charley Bass, who at the time was reading European existentialist philosophy, used to tease some of their more zealously devout friends. One of them was a card-carrying fire ’n brimstone Baptist boy named Job Hawkins. (Leo could never fathom that somebody had actually named their own flesh-and-blood kid “Job,” right out of Judges or wherever it was–Job!) Whenever Job would fulminate to Charley about how certain it was, due to his incessant blasphemy against God and other sins, that he, Charley, would be crisped in hell on Judgment Day, Charley and Leo used to sing him a little ditty of Charley’s composition. They’d stand side by side, hands folded before their chests in mock prayer, and ground it out basso profundo like monks working the low end of a Gregorian chant.

“What in hell could God possibly be? Where in God could hell possibly be?”

“Who in the world could possibly give definitive answers to such infinite questions?”

And then, finally, just to poke at their fundamentalist friend a little closer to the fundament:

“And who but the Devil could possibly believe the things Job does to his little sister?”

During Charley’s more overtly spiritual days, in the late ’60s and early ’70s, Leo used to argue with him now and again about God and the import of Charley’s mystical (but, to Leo’s way of thinking, sheerly pharmacological and wacko) experiences. In a funny, wistful sort of way, just as he’d earlier envied Charley’s devil-may-care wildness, Leo now envied Charley’s daring loss of face among their friends, the renegade glamour of his “altered states of consciousness,” the romantic halo of his sudden sincere ardor for God. “St. Charley of the Harley,” he sometimes teased him; but to Leo, he was a kind of venerably pious James Dean. Leo himself always felt so, well, constricted, so burdened with patrilineal expectation, that he would not or could not allow himself the freedom to explore life with such abandon.

He never let on to Charley how he felt, though. And, as if in compensation for his uncomfortable hidden sympathies, Leo always made sure to snort all the more cynically during their conversations about religion and such.

Neither of them had ever won a single one of those debates. Eventually, at least to some degree, Charley had become sour and rather silent about the whole matter. So Leo, disinclined to pursue the subject further on his own (and secretly fearing he’d get nowhere anyway), had persisted in his conclusion that God was at best inconsequential in human affairs.

In the pragmatic Stokes tradition, however, he did appreciate the virtue of consequential matters, even if they were illusions or mere appearances. His father, Abner Stokes Jr., hadn’t really cared for spiritual things either. But he’d gone to church religiously every Sunday, primarily to keep good standing in the community and only secondarily–or so he told Leo–to placate Leo’s mother, Agnes, who was always conspiring with Nan to secure the salvation of her husband’s immortal soul.

As far as Leo could surmise, Nan and their minister reckoned that, when the accident happened, Abner Stokes was just barely, if at all, in the doorway of the elect. Thus, upon inheriting his father’s role as the upstanding owner of the principal local bank, Leo figured he’d best begin attending church services regularly simply to serve as the local cornerstone he knew he was expected to be.

He could tell it made a difference. People noticed Leo. His being at church every Sunday helped them trust him. And everybody from sharecroppers to cotton planters to J. N. Pippin with his Cadillac-Olds dealership made it a point to bow his head with just a bit of a nod when he walked into Leo’s office at Cotton County Regional Bank looking for advice or a little munificent sympathy.

“Leopold Stokes! What in tarnation are you doing on that floor? Let go of my foot, young man!”

Leo looked up, blinking through his drying tears.

It was Nan!

For the second time that night, his mouth dropped wide open. “Nan! You’re back! You’re alive! Oh God, I can’t believe it! I just cannot believe it!”

Nan was standing with the ball of steel wool in her right fist, the heel of her palm resting on her hip so as to keep the wet wool away from her apron. The casserole dish, still not cleaned, was in her left hand. Leo looked at her hands and arms, then her head, then down her whole body, right to her feet. She was all there. Nan was fine!

“I said to you, Leopold Stokes, let go of my foot! I mean it!”

Leo sprang back, letting go of her shoe and raising himself up to sit on the floor with his legs underneath him. He was weeping again, inwardly thanking God and Jesus and whoever else had answered his prayers, and making a mental note to find some way to refinance the mortgage on that little church. His body was shaking with gratitude.

Nan turned back to the sink, muttering, “Never been so mortified in all my born days!” She continued with her dishes.

Leo just sat on the floor, sniffing with joy. First he noticed that there was not a trace of soot or ash anywhere in sight. Then he noticed Nan wasn’t smashing dishes into the drainer anymore. He wondered how long he’d been lying there on the floor, lost in thought. It could’ve been fifteen minutes, or only five seconds; he had no idea.

“Nan?”

“What do you want from me now?”

“What happened before you noticed me, lying there on the linoleum–”

“Holding my foot like some kind of devil-worshipping sex pervert? I cannot imagine what is going on with you, Leopold Stokes!”

“Yeah…yeah…I know that, Nan. I mean, I’m sorry, okay? I don’t think I can explain it exactly–but, Nan, what happened right before that?”

“I don’t know! All I know is I heard you smashing your fist into that dining room door for some fool reason. I turned around to ask you what in the world you were doing, boy, and you just stood there and looked at me like I was a ghost or something, and the next thing I knew you’d thrown yourself on the floor and grabbed me by the shoe!”

Nan eyed him suspiciously. “Are you all right, Leopold? I tell you what, seems to me this is just one more sure sign you are wanting a woman of proper age and disposition to provide you with feminine companionship. And I’ll tell you this too: if you ever take such liberties with my person again, Leopold Stokes, well, no never mind what I told your momma, I will have to find myself another place to call my home!

“And at my age! Can you imagine that? That would be a true scandal in this little county seat, and I don’t think a man in your position would be wanting such a thing to come to pass. Can you imagine what Constance Cunningham would say to that? I wonder how long you could continue to take her attention for granted–”

Nan carried on with her harangue, oblivious, as she scrubbed away at the forks and knives. Leo grinned, wiped his nose with the cuff of a shirtsleeve, and rose to his feet.

“Good night, Nan.”

She was still talking to herself, or whoever, and did not notice as Leo beamed at her with more love than he’d probably felt for her since he was in actual fact dressed in short pants. Smiling, he then turned and walked through the dining room toward his bedroom to retire.

12. Calibrated Karma and

Halfway Worlds

This time Leo didn’t even call ahead. He didn’t clean up his desk. He didn’t notify Ernestine Elkins. He didn’t close his briefcase, didn’t even bring it along. The moment Leo realized he had to see Charley right now, he just stood up and walked out the door of his office, down through the lobby and out the front door, to the parking lot, where Joseph was waiting by the car. Joseph had the back door open for him by the time he got there, so he didn’t even pause. He just climbed right in and settled down for the drive.

His mind was churning so much it only dawned on him a few minutes later that he hadn’t even told Joseph where to take him. He looked out the window. They were on the road to Raleigh, all right.

“Joseph?”

“Yes, suh, Mistuh Stokes.”

“Where’re you taking me?”

“Down to see Mistuh Bass, jes’ like you tol’ me, Mistuh Stokes.”

“I did?”

“Yessuh, Mistuh Stokes, right when I was cranking up the car.”

“Oh. Thank you, Joseph.”

“No problem, Mistuh Stokes.”

“Whew!” Leo whistled to himself, then muttered under his breath, “Dang, I’m losing it again!” He had no recollection of having said a word to Joseph.

As they drove along, he wondered. Could Joseph have known psychically what Leo wanted? Or had he, Leo, in fact spoken to him, and was he so brain-crazed now by Ultimaya 1.0 that he was forgetting things that had happened just minutes before?

He decided to try his utmost to keep his attention on the road. He wanted to make sure they stayed in the same world in which he’d just read about Bob Jackson’s tragedy at Cardinal Bank. Maybe there was some sign he would see that would tip him off, if they were, in fact, leaving the world of Stokesland and Ultimaya 1.0 to reach Charley’s office in the real world of Raleigh.

One thing for sure: Charley, whenever and wherever Leo might see him, was reliably living in the real world. And he’d give Leo some straight talk about what was really happening.

Of course, now that he thought about it, Charley Bass the Flower Power Acidhead of the old days was never famous for being grounded in reality. And then, how did Leo know the world of Ultimaya 1.0 and Stokesland was actually the same as the place he’d just been when he saw the newspaper at the bank? He hadn’t watched to see if there was any dividing line on the way in to the bank. Like a fool, he’d been watching I Love Lucy!

In that moment, it hit him that he’d again been lost in reverie for–who could tell how long? He looked outside. They were already in northern Wake County, only about three-quarters of an hour from Charley’s office.

“No way!” he thought. “There is absolutely no way I could’ve been drifting around in my own brain all that time. So either Joseph flew down here, or somebody’s continuing to play with time as well as space on me, or I am really losing it. Extra real bad.”

At that point, he gave up trying to keep track of anything going on either inside or outside his brain. After a few moments, Joseph stopped the car and opened the door for him. Feeling like a zombie, Leo stepped out, walked into Charley’s main store and up the stairs, not saying a word to the couple of salespeople who greeted him, and then on into Charley’s office.

He knew Charley would be there, and sure enough he was, sitting behind his desk in a cloud of Winston smoke. He looked up, a bit startled to see someone barging into his office, then grinned.

“Hey, Stokes, what brings you here? Come down to celebrate the fall of Cardinal Bank? Big story today, huh?”

Leo’s smile was thin and pallid. “Naw, that’s not why I’m here, Charley.”

“Well, what’s up, then?”

Charley’s immediate mention of the disaster for Bob Jackson’s bank had caught Leo off guard. He tried to pull himself together and proceed with his plan. Sitting down, he described, with as much enthusiasm and detail as he could muster, the astonishing results of his wishes for a new place to live–the manifestation of Stokesland.

Charley didn’t bat an eyelash the whole time.

Finally, Leo asked, “Charley, you believe what I’m telling you?”

“Yeah, I believe it. I can even see part of it right off. You’re looking a little muscular for the first time since we worked in the lumberyard summers during high school–though you definitely got that Freon anti-glow again, despite your tan. So I believe it. What of it?”

Leo could hear an edge in Charley’s voice and see a wariness or something, he wasn’t sure what, in his eyes. But he went on with the plan.

“Tell you what. Why don’t you just take a look out your window at that parking lot you got for a view here?”

Charley stood up and went to the window. “All right. Now what?”

“See that black chauffeur standing next to the big white Bentley?”

“Yeah. Nice car. What about it?”

“That’s my car, Charley!”

“Okay. So?”

“It came from Stokesland down to Raleigh, Charley! We drove it down from a whole other world that didn’t even exist a few days ago!”

“All right–but ‘exist’ is a pretty big word, Stokes. The world was already a lot wilder and weirder than you thought before Ultimaya 1.0 interrupted your dreams of interest rates and foreclosures. What else?”

“That guy, Joseph. My chauffeur. Says he’s from ‘the Deep North.’ Wherever that is–he sounds like a chitlins and southern fried chicken black man if I ever heard one, but that’s where he says he comes from.

“I mean, there’s a whole bunch of folks up at that mansion I’ve never seen or heard about before. I don’t know where they came from at all. But, lookit, that guy appeared in Stokesland and now he’s here in your parking lot. You could go up and talk to him!”

Charley was unmoved. “So what, Leo? I got better things to do than interviewing chauffeurs from other worlds–if that really is who he is and what he does. So what? You gotta understand something here–I already accept that the world’s got more sides than it’s got corners, and more corners than it’s got sides; it’s full of weirdo surprises. I already know that. I told you that the first time you came down here and told me how you incinerated Nan in your kitchen and then pulled that southern-fried-spinster, Lazarus-outta-the-linoleum stunt. What else?”

Leo pulled the small black velveteen jewelry box out of his pocket. “Take a look at this, Charley. This oughta convince you that Stokesland is a reality and that dreams really can come true. ’Cause I don’t think you quite get it yet. You say so, but take a look.”

He opened the box with his right hand and displayed the ring to Charley with his left.

“Hm.” Charley picked it out of the box. “Intense rock, all right.” He turned it over, looking at the underside of the band, and then examined the stone more fully. “Not like any ordinary diamond I ever saw, that I’ll grant you. Where’d you get it? And how?”

“Nan brought it to me yesterday. She and Joseph and one of the maids picked it up while they were out shopping. Said she got it in town.”

“You didn’t happen to ask what town?”

“I assumed she meant Ashlin.”

“Well, old bud, in your new line of work, or life, I wouldn’t bank on assumptions.”

Charley eyed Leo coolly.

“Did you bring this ring down here just to impress me–like the car and the driver?”

Leo thought about it. “Well, yeah, partly. But I guess for some reason I just like to carry the ring around.”

“To keep your eye on the prize, trying to get Constance back?”

“Well, yeah, that’s a lot of it. But…I don’t know. What can I tell you: the ring just gives me some kind of special strength I feel I need right now.”

Charley suppressed a grin. “I see. Say, Leo, you didn’t by any chance happen to read Lord of the Rings back in the old days, did you?”

“What?”

Charley sighed. “Never mind, skip it.” He lit a cigarette and sat down behind the desk again. Neither of them spoke as he took a couple of slow draws and exhaled fat, tumbling smoke rings. Then he eyed Leo again. “Listen, Stokes. It’s obvious to me that the program is still in charge. It’s obvious that you’re still in a sinkhole of obsession with what you think it’s gonna give you. And it’s obvious that you’re hurting pretty bad, coming down here and trying to impress me, of all people, with hoodoo-voodoo amulets and ‘the Brother from Beyond.’ All that level of it, to me, is a grade C sci-fi flick. What’s up, Leo? What do you want?”

Leo sighed. He sat quiet for a few minutes, wringing his hands in his lap, unable to say anything cogent. Finally, he replied. “Yeah, you’re right. I’m happy about all the good stuff, the house–and you should see Constance, I mean, she’s so gorgeous she’d blow your mind. But there’s this nasty underside I can’t seem to get out of the program’s system. Or out of me. I don’t know why it has to be that way. And I don’t know what to make of things anymore. I don’t know where the real world stops and the world of Stokesland, the world of Ultimaya, begins. Everything’s gotten pretty crazy.”

“Well,” Charley said, “that I can work with. How about just telling me what’s happened since you were down here last. And don’t leave out the underside and the craziness, hear?”

So Leo recounted the whole story, bringing Charley up to current, including the real reason, the way he saw it, for the headlines in that morning’s paper.

When he finished, Charley leaned back in his chair and lit another Winston. “Hm. Pretty weird, all right. I mean, that is the way they say karma works. You set certain consequences or results in motion through your intention, your desiring, your actions. They keep on going, until and unless another motion deflects them. Repeating themselves, with equal and opposite reactions getting set up besides. Mind makes events, eventually. Or so they say in the books. But who knows what causes how much of what? The world’s like a wavy-mirrored funhouse. There’s so many different factors influencing any given moment that usually we can’t see it all. And it’s all kinda slow, kinda vague, how things turn out and why. It takes a lotta time or smarts to pick up on the fact that you’re setting yourself–or even somebody else–up for the equal and opposite reaction to whatever you’re doing, thinking, or feeling, and for a whole lotta repetition too. Somewhere, somehow, you’re not only gonna get something like what you want, but sooner or later, maybe even beforehand, you’ve set yourself up for the backlash as well.”

Charley leaned forward again, eyeballing Leo square on. “So, Leo, I’d say that little devil of a program is delivering exactly what it promised. No breach of contract whatsoever.”

Leo sat quietly. He couldn’t exactly make out what Charley meant but there was no point interrupting. Another C.B. III sermonette.

Charley gazed out over the cars in the lot and continued. “Now, what you got going on here is kind of like what we’d call in the old days ‘instant karma.’ Maybe it’s a function of the machined quality of this program. Maya in the form of a computer program, producing karmic results that are electronically calibrated or something–we’re talking machine-tooled, precision karma here.”

He looked hard at Leo again. “I mean, that thing with Constance’s teeth and what happened to Helen. And Cardinal Bank. Pretty amazing stuff, Leo.” Then he frowned, shaking his head. “And pretty rotten too. I am sorry to hear about Helen–I once loved that girl, you know–and the whole thing with Constance and Ralph. I didn’t know how you felt about Bob Jackson–all that’s a real drag. A lot of it downright tragic, Greek chorus stuff, I’d say. And hey, I’m not about to skip the ‘I told you so’ factor. I did warn you about this little devil, didn’t I?”

Leo thrummed his fingertips on the desk, agitated. He could tell Charley was on another roll and he might as well just let him yap on for a while until he could get him down to the business at hand.

Sure enough, after tamping out his most recent cigarette, Charley folded his arms on the desk and resumed. “Leo, all this about the real world and where it stops and starts reminds me of this guy I knew back in the late sixties. He was a shrink, young guy, working at the Duke University Hospital. We took a few trips together–classic ones, did the whole Alpert-Leary Millbrook ‘set‘’n setting’ bit. Had some wild experiences. And I remember one night we were reading The Tibetan Book of the Dead where they describe the ‘bardos’–the transitional realms of desire, craving, and fulfillment that you apparently rattle through like a runaway train after you leave the body, when you die.

“Well, that Tibetan description ain’t fun by a long shot, and me and this guy got into some strange spaces there. But eventually things cooled out, we were able to help each other through the bizarre hallucinations.

“Finally, as we’re coming down, the guy starts laughing like crazy. He tells me, half-joking but the other half serious, that it just hit him: the bardos are halfway worlds. Like halfway houses for nut cases, see? He says to me that when you’re a loon in a halfway house, you know you don’t really belong there–I mean, these joints are nothing like ‘home’–but, still, you gotta earn the right just to hang in there in one of them every day of your life. And you always got the very distinct knowledge and explicit threat from the Big Nurses and all the orderlies and doctors that you could get shipped off to some place much, much worse. A real-life version of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

“Well. Even when things are going good in one of those places, you never quite get all the way there. You never fully arrive in a halfway house. You’re always at a distance from the real world and always in transit, at least a little. You’re only half, or less, only some itty-bitty fraction of where you really are or could be, or of what you really are or could be. And what would the world be like if you were whole and really real?”

Leo was looking out the window.

“Anyway, sounds to me like you tied your butt into one helluva halfway world, Leo. You don’t know what’s right side up or upside down anymore. ’Course, the whole point of the ultimate wisdom is that this is a halfway world too. Ain’t nothing but halfway worlds until you get enlightened. And even then, it isn’t the worlds that are whole. It’s how you meet them, one instant after the next.

“Which gets me to my main point, thank you for listening, O Great Master of Stokesland Manor. I tell you what: you don’t need a computer technician to help you out at this juncture. I think you need a shaman. You need a guru. You need somebody who’s got a whole other kind of grip on the weirdness of the world than someone like me. You don’t need a computer consultant. You need a Zen master, someone who can put you in touch with the actually real reality–and I don’t mean some slick-talking TV preacher. I mean someone who can work deep in the spiritual and psychic substrata of the world, someone who can set you up with serious divine protection–’cause, buddy roe, you sure as hellfire do need it!

“’Course, you’d have to give up your whole thing in return; I mean, you can’t have this kinda cake and eat it too. You need to go on a psychic diet real fast, Leo, and drop some serious karmic weight.”

Charley eyed Leo. Leo’s eyes were rolling skyward.

“I mean it, Stokes. If what you think is happening to you actually is happening, then karmically you’re not that far off from one of the old heroes of Tibet, Milarepa. Long story short, his momma went on a vengeance rampage against an evil uncle. She insisted Milarepa learn the black arts; he was still a young guy and didn’t feel he could refuse. Turned out he had quite a talent for it. But after causing hailstorms and other heavy stuff, his coup de grāce was magically bringing down a stone house on the uncle’s entire family on the occasion of the daughter’s wedding party. Killed thirty-five people.

“That’s when it dawned on Milarepa that he was seriously up the karmic creek, no paddle, not even a boat. He found a super-powerful spiritual adept to straighten him out, guy named Marpa. And old Marpa had to have him half-build and then tear down about a dozen giant stone houses all over the countryside, by hand and by himself–no magic!–to release those karmas. Sarcastically called Milarepa ‘Great Sorcerer’ and kicked his butt endlessly. Marpa only let up when Milarepa, with his back breaking and hands bleeding from hauling all those boulders around the county, was about to kill himself in despair. When he did let up, Marpa said it was too bad, the purification wasn’t quite over; if only Milarepa could’ve suffered through one more house going up and coming down by his own backbreaking labors…

“Well, Stokes-ey, old bud, I don’t think you’re a Milarepa but I am definitely no Marpa. So I’d say you need some big-time spiritual help in your life right about now–and on a whole other level than proper old Wellington at your Episcopal Church in town or even those faith-healing, Bible-thumping Strap Rock boys can give. You need someone who can plug you into the presence of the actual God. Who or Which by the way is not reducible to the pictures those folks broadcast in their churches and what the really Big Dog Believers televangelize.”

Leo was steaming. What any of this had to do with him, he had no idea. “Mountain Man, could you can the goldang sermon and philosophizing? What in the world does some dude in Tibet a zillion years ago have to do with you and me, here and now? Get outta your head, Bass, and help me out right here. Earth to C.B. III! I got a ring in my pocket and now, after twenty years of her dying to get hold of me, I can’t get the dang thing on Constance’s finger. What’s a shaman gonna do about that? Shoot, I don’t even know what a shaman is. What kinda nonsense are you talking to me?

“I got Nan thirty years younger than she really is, twenty times sweeter than she really is, and all of a sudden she starts looking real good to me. Nan! Jesus, it feels like incest or something; this is weird stuff, Charley! What’s a Zen master gonna tell me about that?

“I got a mansion full of priceless art and high-priced servants and I don’t have a hen’s brain of an idea where it all came from. And I got some poor innocent woman kicked toothless and trampled to death by her own horse and her husband now cozying up to my lady, ‘consoling’ each other!

“’Scuse my cracker ignorance, but I don’t think this kind of stuff is on the contract when people go find medicine men and gurus to bliss out in the ozone somewhere, Charley. You tell me all this craziness I got going on is right on target for what I asked the dang program to give me, which makes no sense to me, but now I have no idea how to ask for anything else and I’m shaking in my boots at the thought of asking for anything at all.

“We can cogitate on metaphysics later. I don’t need God. I don’t need a guru. I need a strategy, Charley! I need a plan.

“What’s all this let’s-go-whine-at-the-feet-of-some-wizard and humbly hope for help stuff? Where’s your good old American cojones? We can figure this dang thing out. You built an empire without even trying! I haven’t done too poorly myself. And now we’re settin’ here tapped into a raw source of world-moving power like nothing we ever even imagined before. And it’s real, Charley! Think of where we can take it. You’re an entrepreneur, man. Look at the possibilities!”

Charley leaned forward over his desk. “You number crunchers and money monkeys are all alike, Stokes. Got about as much interest in the subtleties of what’s going on around here as a fat redneck attacking a platter of barbecue.”

Leo also leaned forward, glaring at Charley, eye to eye. “If you’re so hot for spiritual truth, how come you ain’t gone to a shaman yourself? What in tarnation are you doing hanging out in computer heaven? You spending your life monkeying with a bunch of circuit boards and raking in cash and me spending my life monkeying with farm and construction loans and raking in cash sounds like the same platter of fatback to me! ’Scuse me, Mountain Man, but if you were so dang hot on getting in touch with the subtler dimensions of things, you wouldn’t be sitting here burying your brains in computers and performing the remarkable charitable act of donating your lungs before you die to the goldang R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company!”

Charley twisted his mouth for a moment, maybe trying to suppress a grin. He looked at the end of his cigarette, then tamped it out. “All right, Stokes. It’s real simple. You wanna know what to do? You wanna know what to ask for?”

End of excerpts

Ultimaya 1.0:

The Trouble with the Wishes of Leopold Stokes

Ultimaya 1.0:

The Trouble with the Wishes of Leopold Stokes